Enhancing Proprioception in Movement Teaching Environments

The term proprioception has several interpretations, definitions and approaches purporting to enhance it, vary somewhat across research, clinical, and conditioning environments. This article intends to clarify the term and considers how proprioception can be approached by movement teachers and practitioners looking to improve and enhance their client’s movement function and performance.

What do we feel?

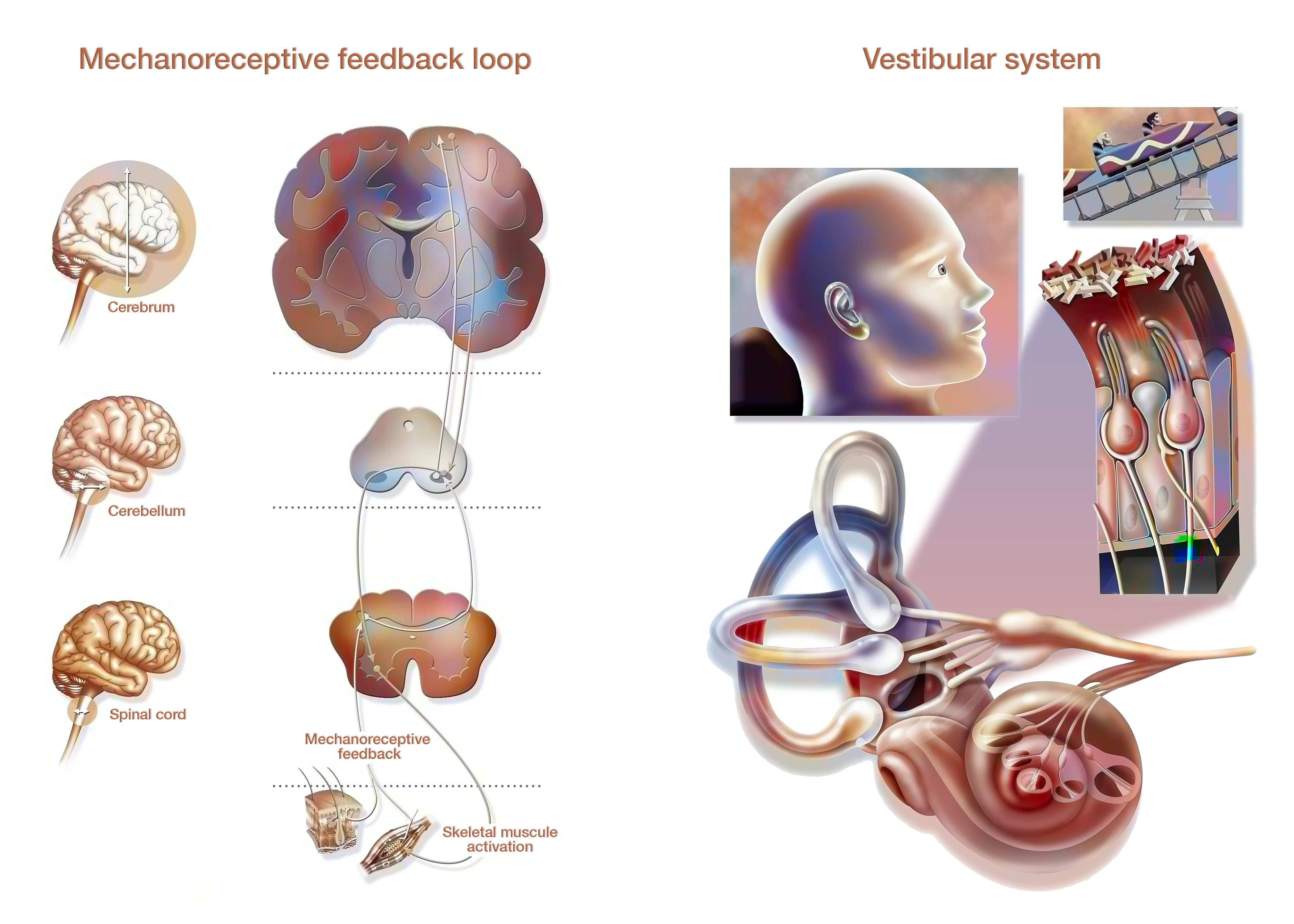

Sensory information elicits the actions we take and the efficaciousness of those actions, it provides feedback essential for motor control and the enhancement of movement skill through motor learning. Specialised sensory (afferent) neurones provide the central nervous system (CNS) with a wide range of information about the surrounding environment and the state of functioning within the body. Aside from the primary exteroceptive senses of sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, we also have interoceptive senses that gather information from within the body, many of which are important for maintaining homeostasis. Key interoceptive senses related to proprioception are those that inform the CNS about spatial orientation, kinematic (motion) and kinetic (force) information1,2. Proprioception is often considered in relation to the kinaesthetic information provided by mechanoreceptors like muscle spindles, Golgi-tendon organs, and joint receptors3. As such, it is commonly defined as ‘perception of the relative position, orientation, and movement of body parts in relation to one another’. However, when including sensory information provided by additional mechanoreceptive structures in the skin, and the vestibular system2, this definition can be expanded to include ‘perception of the orientation and movement of body parts in relation to the surrounding environment’. Such a definition is more in keeping with Sir Charles Sherrington’s original description (1906), that proprioception is a perception of joint and body movement as well as position of the body, or body segments, in space1,4,5.

Sensory acuity

Differences in definitions ultimately boil down to which sensory information is being considered under the umbrella of the term. If proprioception is a sense of something, it must be more than information alone. Whichever sensory neurones are being considered, the afferent information they provide is simply raw data, to sense this data it must be processed by the CNS. What and how this information is processed is dependent on many factors. Perception that arises from proprioceptive input is governed by genetic predisposition, prior experiences, and acquired motor learning4. It is therefore important to consider how someone’s previous experiences may affect their ability to respond both consciously and subconsciously to feedback provided by their sensory system. Lack of sensory experience, awareness and understanding of one’s physical self in relation to the environment or the task at hand, is one of the primary reasons for not being able to complete a task successfully. Even tasks as familiar as walking require real-time kinaesthetic sensory feedback to be executed effectively. When it comes to learning new tasks, sensory familiarisation is an essential part of the learning process1. Strategies for developing sensory acuity in conjunction with neuromuscular patterning and physiological development should be an important consideration within any training agenda focused on improving functional movement performance.

Training awareness of what, for what?

Enhancing ability to accurately sense the body’s relative position and movement in space will logically have a positive impact on developing movement skill and performance potential. However, it is important to understand that sensory experiences are as specific as the motor responses they inform1,6. Specificity and relevance of proprioception training strategies are therefore as essential as they are for motor programming or physiological training strategies and any training task set for proprioception development, should do so in conjunction with related motor learning agendas. Exteroception, communication, task comprehension and prior experience, all play a key part to the cognitive stages of learning2, so they too should be considered in relation to the wider aspirations of the learner. Above all, any implemented training tasks should promote the development of motor programmes and schema that are relevant to the practical application they are being developed for. Often so-called proprioceptive training exercises fail to consider the relevance of the sensory inputs they are drawing upon, or the movement patterns being developed beyond the scope of simply being able to perform the exercise proficiently. To maintain validity, exercises should always relate to the acquisition of the training outcomes they represent, and those outcomes must relate to a structured plan of SMART goals.

Putting it into practice

Essentially any strategy that focuses attention or places greater reliance on interoceptive senses related to spatial orientation, kinematic and kinetic awareness, will be training acuity of proprioceptive feedback. Balance training exercises are probably the most obvious method that springs to mind when movement teachers, trainers, and therapists focus on proprioceptive development. A quick internet search will confirm this, bringing up a plethora of balance focused exercise ideas with vastly varying degrees of validity or usefulness. Balancing forces acting through body parts and the contact points with the environment, is a fantastic way to heighten demand on proprioceptive feedback. This sort of training works on both a conscious and subconscious level, developing motor patterns that provide solutions to the challenges presented by the exercise. This is a non-linear or constraints led approach to developing motor learning in conjunction with proprioceptive feedback. Valuable as this approach is, be aware, there is a tendency for exercise strategies to veer away from subject relevance when it comes to balance training approaches. Try not to fall into the trap of creating technically challenging exercises that bear no relevance to functional demand. Remember circus trick are for circus folk! Balance exercises need to start with simple biomechanical processes that have simple movement sequences (kinematics) and low loads (kinetics). Progression needs to maintain alignment with movement patterning pertinent to the subject's functional requirements.

Before jumping into balance training approaches there are other places we can start. Simply shutting the eyes while performing a physical task or exercise is a great place to begin. Pretty much, any exercise can be performed with visual feedback removed to enable the mind to tune into the other sensory information competing for the CNS’s attention and response. Just ensure doing so does not increase the chance of sustaining an injury! Also remember, the joint and movement strategies of the training task should be functionally relevant to SMART goals that inform SMART training strategies. Being able to do a pointless exercise in the dark is still pointless!

To get started, try the following examples and if you would like to develop your understanding of this and other topics, check out the exercises, tutorials and live events included in our professional membership area.

Blind Cat in the mirror

I’m sure you are familiar with the Cat exercise and the many variations that are taught. I’m also fairly certain that when doing this exercise (or any other four-point kneeling exercise for that matter), that you have a sneaky check in the mirror, if one’s available to check your neutral spinal alignment is correct (especially if you are a teacher). Typically, if we can tap into it, we will use visual feedback to refine our technique and form, especially if it has been highlighted as important when we were taught the exercise. The same would be true for postural refinements in general (but that warrants a whole post of its own!).

- Use a mirror to set your best neutral spinal alignment (there’s another post right there!) in four-point kneeling. If kneeling doesn’t work for you, then try standing, bent forward with the arms supporting your torso on a raised surface.

- Then shut your eyes, take a moment to tune into the feelings and sensations you have in that position. Beyond focusing on your sensory experience, also try to focus on how you feel as a whole; physically, emotionally, a collective state of being.

- Open your eyes and check everything is still where you left it. If not repeat the process until you have a consistent start position.

- Now shut your eyes again and take your spine into a fully flexed position, tucking the pelvis and head in too. Sequencing is unimportant at this stage, stick with your favourite version. Then bring your spine into a fully extended alignment, same protocol, keep those eyes shut!

- Repeat the action two or three times more, then bring yourself back into the start position. No peeking! Feel your way back by recalling the vividness of the whole experience you took time to acknowledge at the beginning.

- Now you can look! How close are you to that initial start position?

- Note the anomalies (if there are any), correct them, then repeat the process three more times.

- Practice makes perfect, well more consistent hopefully at least!

- To progress, try other movements and spinal alignments checks.

- To progress further, move on to apply the process to dynamic movement sequences. You will need to video yourself for this or better still ask your teacher to help you with feedback. Just remember that the exteroceptive feedback needs to be turned off as much as possible for you to tune into the interoceptive experience.

Single leg balance board (or Bosu) step-up

Safety first: Only attempt this exercise if you have good balance already and have someone spotting you or at the very least are next to something solid that you can grab if you lose your balance. As with all online unsupervised exercise suggestions, you attempt them at your own risk! For those of you who are at all unsure about safely attempting this exercise, try it on a thick pile carpet or a folded over exercise mat instead. This is still an unstable surface and while more focused on control of the joints of the foot it will serve as a useful alternative.

- If using a balance device like a balance board or Bosu, ensure it is on a nonslip surface and for good measure make sure there is a nonslip mat on the surface of the device too.

- Now place the ball of one foot over the balance point of the device.

- Transfer your weight (centre of mass) onto the ball of that foot, then step up onto the device and balance there for a moment.

- Do not spend longer than 20-30 seconds in the balanced position as fatigue will cause substitute patterns to be adopted and therefore change the sensory feedback.

- Remember, we are focusing on developing sensory awareness, so you need to tune into the experience in the same way as the blind cat exercise above. BUT keep the eyes open for now!

- Repeat the stepping up and down action between 4-8 times before switching legs.

- You can repeat two or three cycles (sets) for each leg.

- To progress, try alternating legs each repetition and shorten the pause in the step-up position.

- To progress further, try with one or two eyes shut (ONLY WITH SOMEONE SPOTTING YOU!).

The big picture

Ultimately, there are numerous theories in the field of movement learning with varying viewpoints on the role and importance of proprioception in the development and enhancement of movement skill, with no outright consensus4. Whichever way you choose to frame it, the concept and value of developing self-awareness within movement learning approaches, reaches beyond the realm of conventional motor control theory, with links to embodied cognition1,7,8, experiential learning theories9,10 and somatic approaches11-12. Encouraging clients to acknowledge, investigate and assign value to what they ‘feel’ in relation to the outcomes of their physical performances, is a fundamental part of a self-reflective approach to learning and demonstrates the importance of proprioception in the development of self-awareness in all movement teaching environments.

References

- Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D., Winstein, C.J., Wulf, G., Zelaznik, H. N. (2019). Motor control and learning: (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2020). Motor learning and performance (6th ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Magill, R. (2014). Motor learning and control: Concepts and applications (10th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

- Han, J., Waddington, G., Adams, R., Anson, J., & Liu, Y. (2016). Assessing proprioception: a critical review of methods. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 5(1), 80-90.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2014.10.004.

- Sherrington, C. S. (1906). The Integrative Action of the Nervous System, Univ. Press, Cambridge.

- Mackrous, I., & Proteau, L. (2007). Specificity of practice results from differences in movement planning strategies. Experimental brain research, 183(2), 181-193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-007-1031-z

- Shapiro, L. (2019). Embodied Cognition - New Problems of Philosophy (2nd ed.), New York, NY: Routledge

- Johnson, D. (Ed.). (1995). Bone, breath and gesture: Practices of embodiment. California, CA: North Atlantic Books.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and Education. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Upper Sadle River: Prentice Hall.

- Feldenkrais, M. (1990). Awareness Through Movement. New York, NY: HarperCollins

- Todd, M. E. (1968). The Thinking Body: A Study of the Balancing Forces of Dynamic Man (Vol. 14). Princeton Book Company Pub.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates.

We hate SPAM too so will never sell your information, for any reason or bombard you with sales emails!